The Food Scene's New Rallying Cry: Improvise, Adapt, Overcome

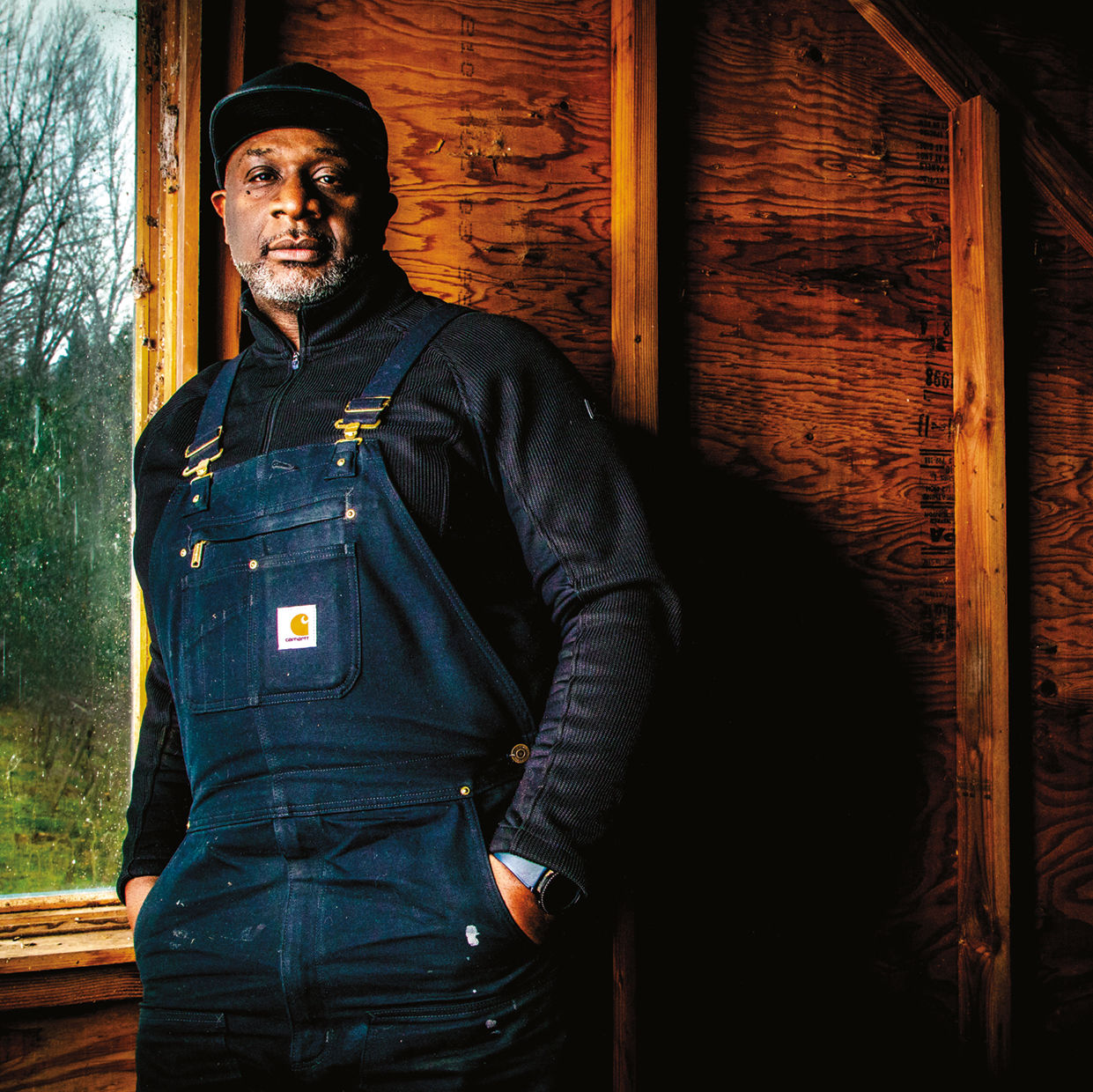

Gado Gado

Image: Michael Novak

Winter is coming. The hellhounds are at the gate. Even the fittest might not survive Darwin’s bite out of the Portland food scene, currently splintered like an old barn after a tornado. There is no clear path, no answers, no silver bullets, no wizards or white knights riding in from the north. A sweeping, save-the-restaurants, FDR-level New Deal would be a miracle, not just for cooks, farmers, and our insatiable palates, but for neighborhood vitality, the state’s economy, and our very identity. So far, the government has shown little interest. And given the Russian roulette of health risks, the perception of restaurants as a magical shared experience is not returning soon. The communal table is dead. Long live the communal table.

A number of celebrated restaurants closed to weather the storm. But the scene hasn’t disappeared, as chefs mount valiant takeout efforts and CSA boxes, love letters to their struggling purveyors: the farmers, coffee roasters, even the flower arrangers. Meal kits and cocktail kits are everywhere. Eric Nelson, inventor of Eem’s swashbuckling island drinks, includes skull toothpicks, umbrellas, and secret tips—everything but the OLCC-banished booze.

But for many, these are emergency Band-Aids on long-festering industry wounds: too much competition, a kitchen talent crisis, rising rents, daily panics to make ends meet. Sadly, COVID-19 will eliminate some of those problems, with Hunger Games fury.

We don’t know who will survive or inspire the future. But a postvaccine future will come, and with it a new generation of thinkers and risk-takers. After all, jerry-rigged kitchens, bootleg salumi, and crazy idealists fueled Portland’s last food revolution. “We might see a cool new period in 12 to 24 months,” predicts veteran Portland restaurateur Kurt Huffman. “Lots of gritty, scrappy, super-interesting businesses. It might feel like postapocalyptic dining, creative in dangerous ways, reminiscent of 10 to 15 years ago.”

Reinvent, reboot, and adapt. That’s the rallying cry right now. “Portland’s food scene was born of out this,” says Han Oak’s Peter Cho, who famously reimagined the Korean restaurant as a mom-and-pop house party in 2017. “Portland was meant for this moment.”

The Malka cooks behind Crisis Kitchen: Eli (left) and Adrian

Image: Courtesy Malka

Malka typifies the new north star for restaurants seeking a larger sense of purpose. For four years, Jessie Aron, a cult gastromasher on Portland’s food-cart scene, was stuck in red-tape purgatory trying to open her dream restaurant on Division, something akin to the kitchen in Hayao Miyazaki’s animated fantasy Howl’s Moving Castle, chaotic and unexpected, but delicious and life-sustaining.

At last, on February 4, Malka opened. Lines formed for next-level zucchini fries and a mysterious pork bowl called Important Helmet for Outer Space. Forty-two days later, the governor’s mandate dropped, pivot became the hot new word, and overnight Malka found itself in The Wire instead of a Miyazaki fantasy, as paranoid people nervously drifted in, picking up to-go bags like addicts getting their fix.

Aron pushed on, making the likes of matzoh ball khao soi—the first mash-up of Passover and Pok Pok. “Someone called me the no. 1 quarantine hot spot,” says Aron. “That was not the dream!”

In between labor intensive dishes, Malka was galvanizing a movement spreading around the city, a pay-it-forward system, where anonymous benefactors gift meals to unknown future diners in need. Initially, the program caught on with working cooks helping to feed industry workers. But at Malka, it’s part of a larger philosophy, a way of life. Based on how much is in the kitty, Aron’s Instagram feed calls out the day’s allotted dishes, free to anyone in need of a good meal. Or perhaps an Important Helmet for Outer Space.

Meanwhile, a kind of micrononprofit dubbed the “Crisis Kitchen” is blossoming inside Malka’s kitchen, from aspiring cooks Eli Goldberg and Adrian Groenendyk. Their eureka: to make good food and give it to hungry people, granola to tofu banh mi bagel sandwiches, using donated ingredients. The duo’s fast-growing “mutual aid network” is not exactly the World Central Kitchen. But it shows how cooks and diners and purveyors might collaborate on a better world. Aron, only 31 herself, calls them Malka’s young revolutionaries. “They believe in social justice. I’m telling you, Adrian will be president one day.”

Malka’s kindred spirit is Pip’s Original Doughnuts on NE Fremont, where generosity was already built into the business plan. The shop’s hashtag says it all: #communitynotcompetition. With their famed made-to-order doughnuts temporarily offline, owners Nate and Jamie Snell spearheaded a new in-house company, Community Chai, bottling “concentrated cups of kindness.” To distribute a portion of the profits, the couple deploys an email chain-letter method, with each food-scene recipient suggesting the next person deserving of support. The Snells personally meet each donee, building new friendships and perhaps future food collaborators. Up next: Pip’s Ice Cream, with flavors like Japanese Garden, made with herbal chai and ceremonial green matcha from the Aichi prefecture of Japan.

“The new reality is a leveling of the playing field,” says Nate. “All these things—the Beard awards, the multiple locations—are not related to our ability to survive. We’re investing in community, paying people a decent wage. This should be the new normal. There’s no more room for predatory entrepreneurs.”

Over at Gado Gado, a different kind of idea is rising: fun in the time of COVID-19. An offbeat drive-in movie theater, postapocalyptic flicks, and flaming-hot-cheese-spiced popcorn may sound antithetical to these sobering times, but it might be a lifeline. It all happens in the restaurant’s Hollywood parking lot, with help from a blow-up movie screen.

Last year, Gado Gado was Portland’s rising food star, a playful mind-bender of Indonesian cooking. Will that restaurant ever exist again? Owners Thomas and Mariah Pisha-Duffly don’t know how the math will pencil out once Multnomah County restaurants can “reopen” with distanced tables and half capacity. For now, they’re reverting to their pop-up roots, creating ephemeral experiences that shout “what the hell, we’re having fun.” That spirit is found in Gado Gado’s takeout mode. No clinical drop-offs here. Pick-up bags await under a music-bumping, disco-ball-adorned tent erected out front. It makes you smile and dance.

“Creativity comes from restraints,” says Thomas. “Now is the time to embrace freethinking. Everything is on the table. We have to entertain wild ideas. Nothing else will get us out of this.”

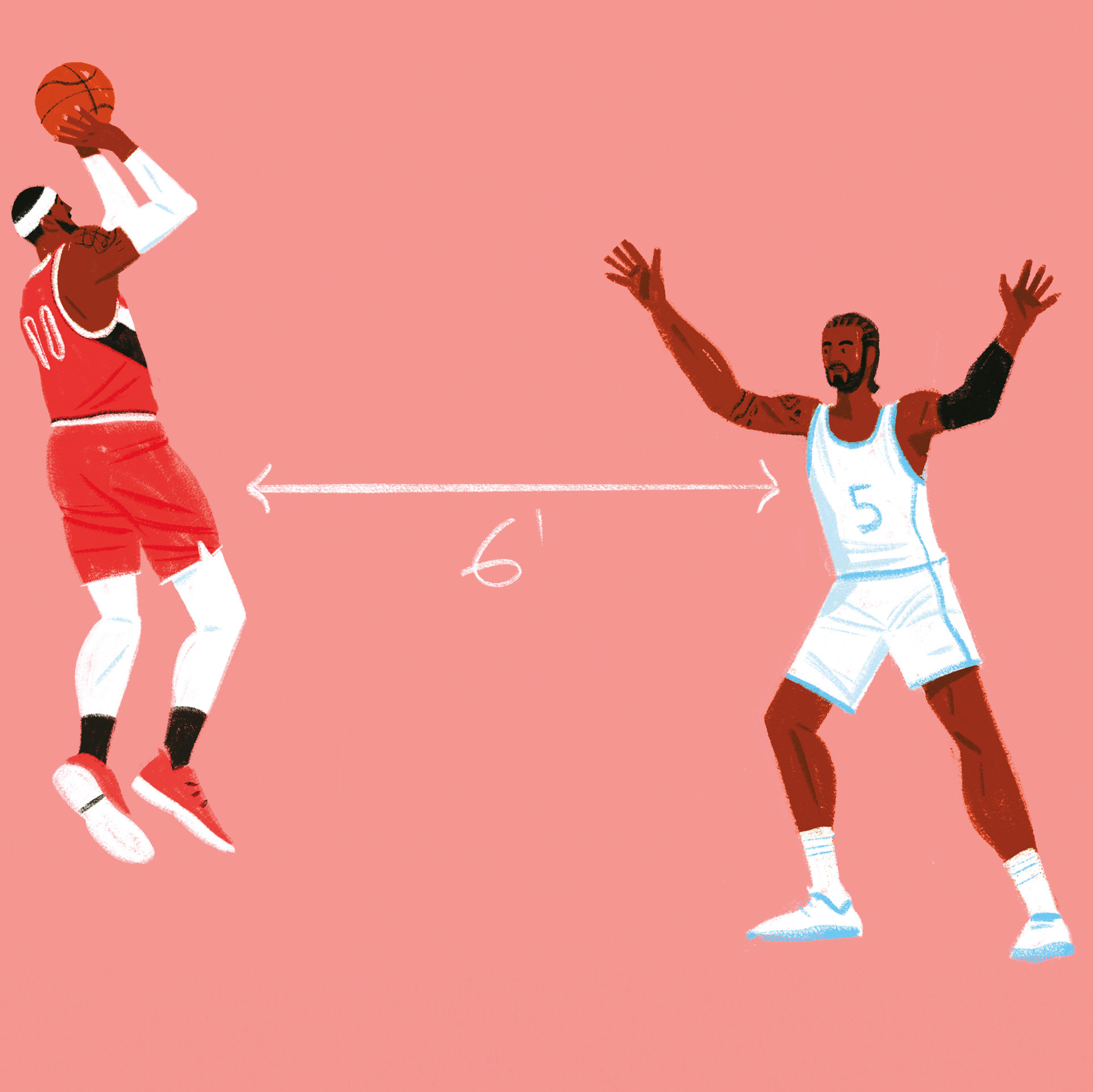

Pip's Original

Image: Courtesy Pip's Original

Portland’s food carts, once icons of ingenuity in money-strapped times, lost their visionary steam in recent years. But a new surge is coming, ready to embrace a wave of restless, laid-off cooks.

Already, next-gen carts like Southeast’s Holy Trinity Barbecue are logging record sales. Steps away, Jojo’s seems to have nailed the food cart recipe for the future: a serious comfort-bomb palate, a BLT flaunting double-fried bacon, food collaborations with food cart friends, and a pay-it-forward program. Posits Jojo’s owner-cook Justin Hintze, “We’re used to adversity. We’re not dependent on alcohol, where many restaurants make their margins. Our business models are situated for this.”

The hardest road ahead may be for veteran restaurants, whose chefs and owners wonder if the new world will still need their romantic dreams. This notion is best captured in a heart-wrenching, thought-provoking New York Times piece published in April by lauded Manhattan chef Gabrielle Hamilton, of the groundbreaking indie-spot Prune. In Portland chef circles, it was a must-read.

“We’re trying to salvage what we’ve done. The next ideas will come from people with nothing to lose,” says Huffman, whose ChefStable group has a hand in 20 local restaurants. Rising rents—and with it, homogenization creep—have put a chill on our restaurant democracy. Now, as vacant spaces loom, doors may open up again for people with clever, low budget models. And Portland, suggests Huffman, will benefit. “It’s going to be very hard. You just prepare as best you can, hope you last and have the strength to go forward. For those that survive the next two years, fun times will come. Can you imagine how people will go bonkers? It will be like V-E Day, people making out in the streets.”