Lore of the Mountain

Image: George Henderson

Each year, some 10,000 people attempt to summit Mount Hood—and since 1896, more than 130 people have perished in the process. For the men and women who pit themselves against this peak, risk is part of the allure. But their desire is also stoked by the stories of those who challenged the mountain long before. Here are five of Hood’s most unforgettable tales.

The Paper Chase In 1854, Thomas J. Dryer, owner and editor of the Weekly Oregonian, trumpeted himself as the first person to ascend Mount Hood’s 11,249-foot apex. But three years later, Dryer’s own employee, Henry Lewis Pittock, climbed to the top and found many of his boss’s claims—such as the presence of volcanic vents on the summit—to be untrue. In an account printed in a rival paper, a member of Pittock’s team surmised that Dryer stood about 350 feet shy of the true summit. Pittock topped his old boss again in 1860, when he seized control of what would become the modern-day Oregonian.

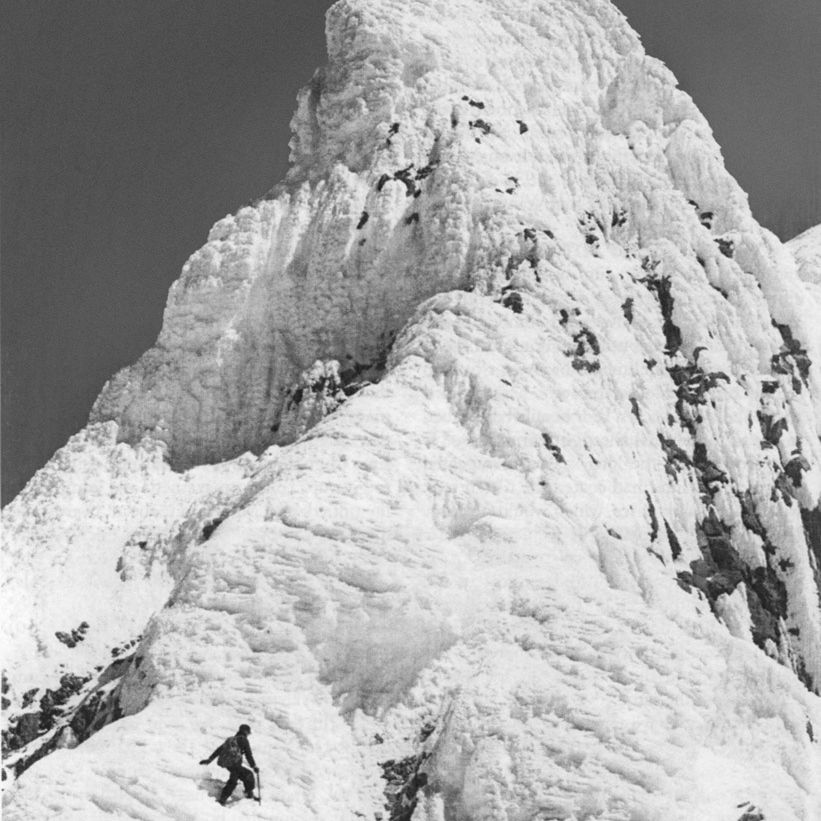

A Ridge Too Far By 1939, only one mountaineering route on Mount Hood had yet to be conquered: Yocum Ridge, a gnarly pinnacle of crumbling rock that guards the volcano’s west flank. Theorizing that a thick wall of winter ice would stabilize the rock, Jim Mount, a member of the elite Wy’East Climbers club, tried the route that winter. Although Mount displayed incredible skill (at one point, he used only a mound of ice to support a belay rope), he could not complete the climb. But his winter-ice theory inspired others to follow, and finally, Fred Beckey—a living legend credited with hundreds of first ascents—crested Yocum Ridge in 1959.

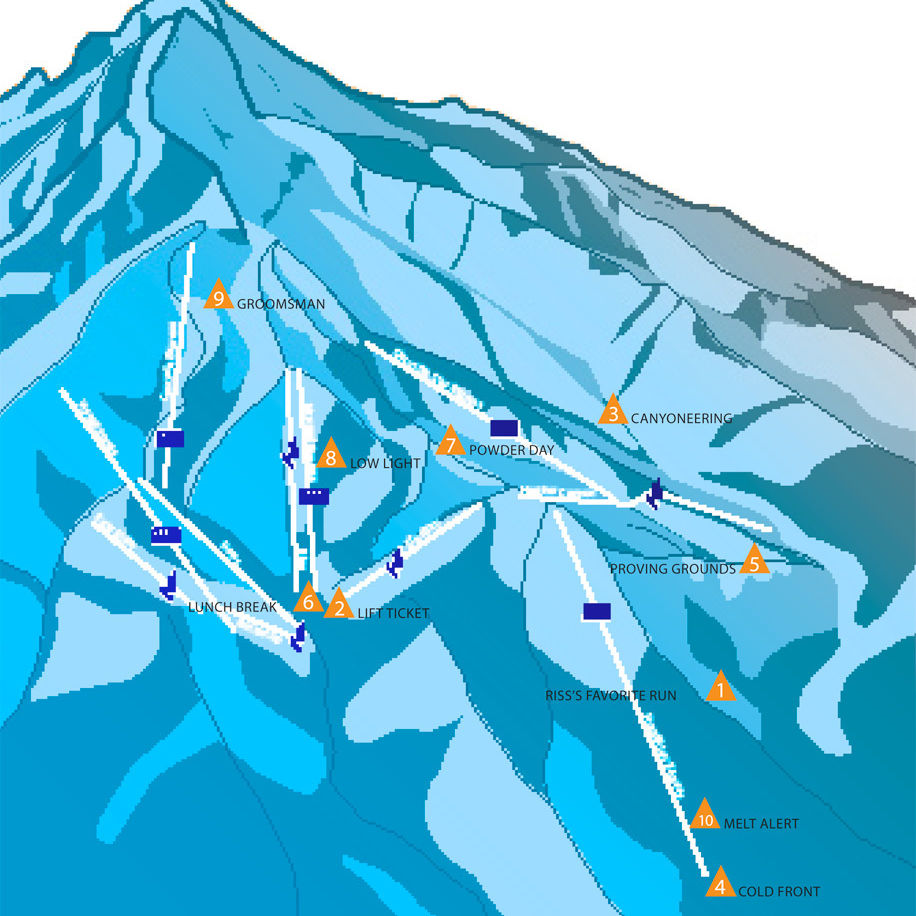

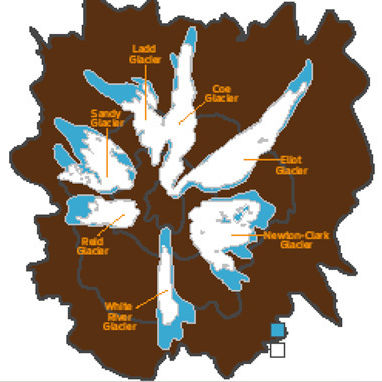

Beast of the East On a bitterly cold day in March 1971, Sylvain Saudan, a 34-year-old Swiss climbing guide, arrived on the summit via helicopter. He was armed with a pair of 210-centimeter skis and a plan to ski Hood’s eastern cliffs. No one had ever attempted such a feat. Just after 4 p.m., Saudan pointed his skis down the 50-degree, crevasse-riddled chute, aiming for the Newton Clark Glacier 3,000 feet below. Despite triggering a large avalanche near the top, Saudan clung to the icy slope using his unusual “seal turn” technique, whereby he leaned so far back on his skis, his shoulders skimmed the mountain behind him. A photographer for a ski magazine was on hand to shoot the deed, but found he had placed himself out of sight. Saudan’s act of daring lives on only in words.

Black Hawk Down One of the mountain’s most horrific events unfolded on May 30, 2002. Caught in a web of ropes, nine climbers were swept inside the Bergschrund, a crevasse located 800 feet below the summit’s south face. Three of them were killed. An Air Force Reserve Pave Hawk helicopter—a modified version of a Black Hawk—was dispatched to aid rescuers. While hoisting a survivor into the air, the hovering copter began to stall. An alert crew member on board released the line, saving the climber’s life. But seconds later, as KGW’s cameras beamed the scene to live TV, the craft careened into the mountainside and tumbled 1,000 feet down the slope. Tossed from the helicopter as it fell, the six crew members survived.

The Lost Trio In the face of hurricane-force winds and whiteout conditions, three climbers—Kelly James, Brian Hall, and Jerry Cooke—reached Hood’s summit in December 2006. The three men were seasoned mountaineers, but the extreme conditions, which besieged the mountain for more than a week, were unforgiving. On December 10, James, injured and huddled in a snow cave about 300 feet below the summit, managed to reach his wife by cell phone for a haunting last goodbye. The story became a national sensation, though to this day no one knows exactly what went wrong. James’s body was discovered seven days later, his bare hand extended to reveal a ring engraved with his initials—an apparent final signal to his family. The bodies of Hall and Cooke remain lost on Hood’s slopes.