The Big Melt

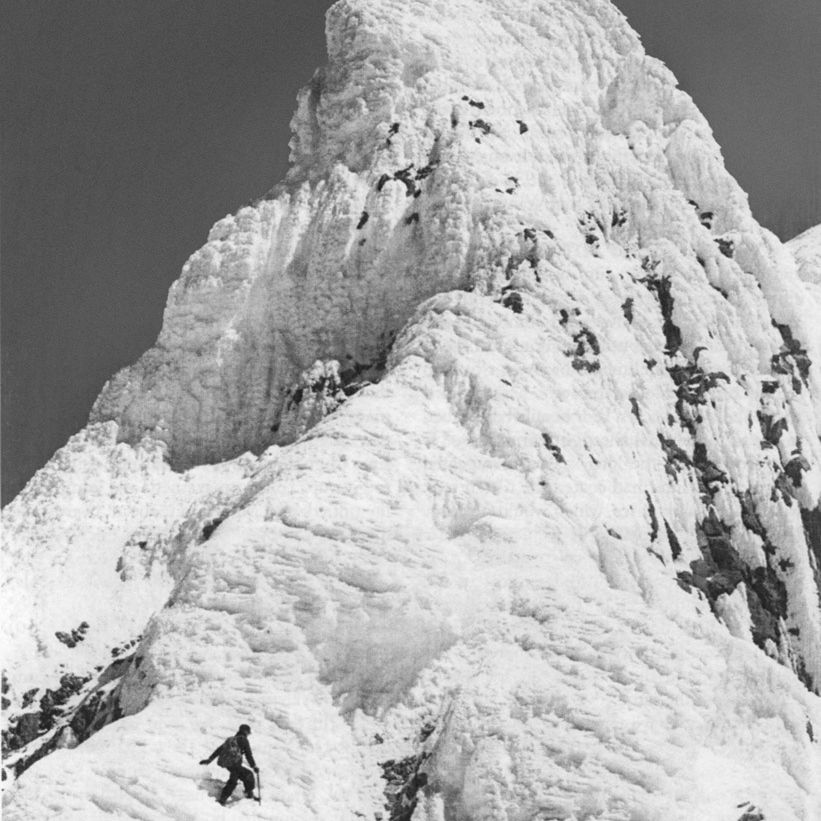

Image: Jessica Keirn

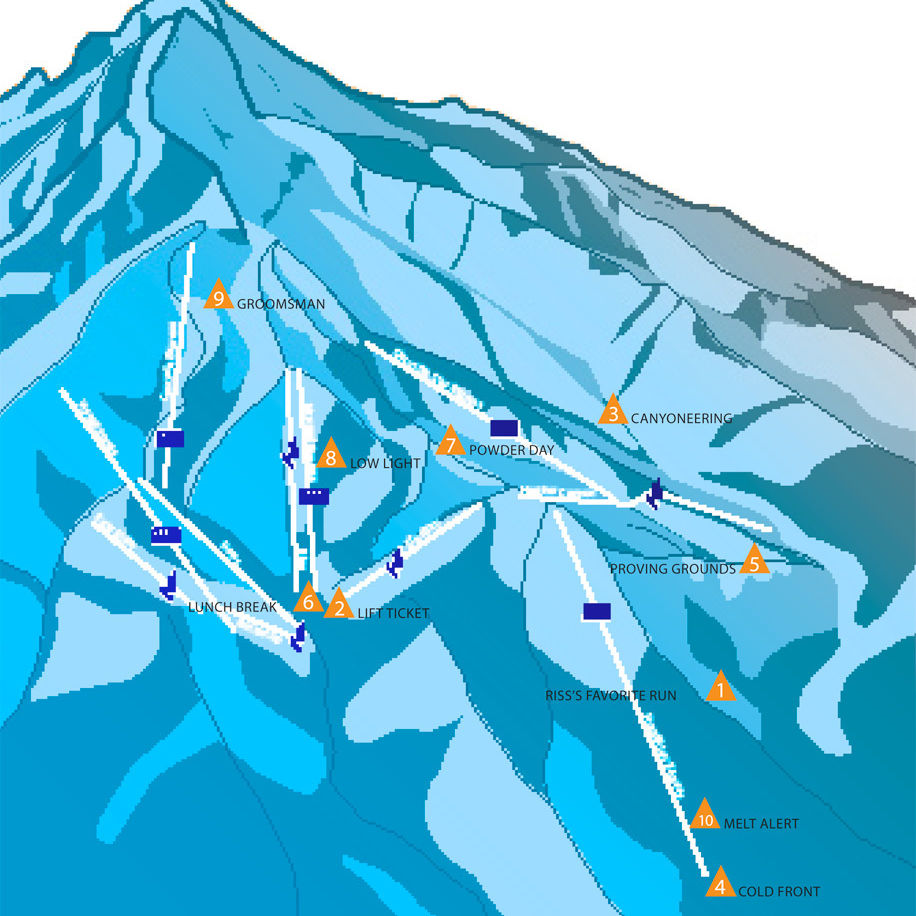

EACH SUMMER, 100,000 skiers and snowboarders journey to Mount Hood’s Timberline Lodge ski resort to plumb the powdery snowfields that linger above 6,000 feet. After all, the resort is home to the only year-round lift-accessible skiing in the country. But it’s a limited-time offer: according to Andrew Fountain, a Portland State University geology professor, “Our children could see summer skiing on Hood go away.”

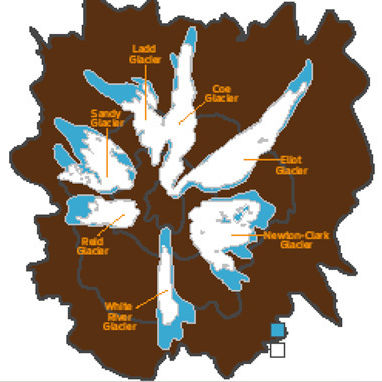

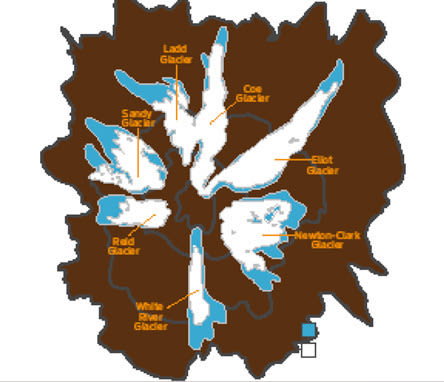

Mount Hood’s 12 glaciers have shrunk a collective 40 percent since 1901, when a geologist from Johns Hopkins University first documented them. And since the mid-1970s, temps on Hood have warmed by about one degree every summer. “That’s a rate of warming that exceeds what can be explained by natural [causes],” says Fountain, who has been studying Hood’s glaciers since the mid-’80s. If drastic measures aren’t taken to curb global climate change, he believes the mountain could see entirely snow-free summers in 200 years—max. “We’re beginning to see it already,” he says. “It’s harder to keep snowpack there in the summer.”

Eliot Glacier has retreated by about 2,200 feet and has thinned by some 200 feet—and it’s one of the lucky ones. Shielded by an insulating layer of rock deposited by Hood’s eroding north wall, it’s lost only 20 percent of its mass. Smaller, more exposed glaciers on south-facing slopes—like White River and Newton Clark— have lost as much as 60 percent of their mass.

However, glaciers on Hood (as well as other Cascade peaks like Rainier) are faring better than those in Colorado, the Sierra Nevada, and Glacier National Park, most likely because of the mountain’s proximity to the ocean. The moist air in the Pacific Northwest means our peaks still get walloped with snow.

But change is already at hand. Remember the debris-choked floods that washed out Highway 35 in 2006? Fountain points to glaciers as the culprit. “When a glacier retreats, it leaves incredibly steep valley walls that are subject to collapse.”

Animals like pikas—those cute, cuddly cousins of rabbits—that live at higher elevations, where glaciers feed water to alpine ecosystems during the summer, are also at risk. As the ice disappears, they’re running out of places to call home.

If that tug on the heartstrings doesn’t convince you to shrink your carbon footprint, an appeal to your stomach might: Eliot Glacier provides a significant portion of the water that irrigates the Hood River Valley’s renowned apple and pear orchards. Once the source of that water disappears, the crops may begin to wither away, too.

Portland’s own water source—the rain-fed Bull Run Watershed—remains healthy, though. Good for us; bad for Hood. “If it was affected,” Fountain says, “we’d have a lot more people interested in what’s going on up there.”