Q&A: Salt & Straw’s Flavor Maestro Tyler Malek

Image: Andrew Thomas Lee

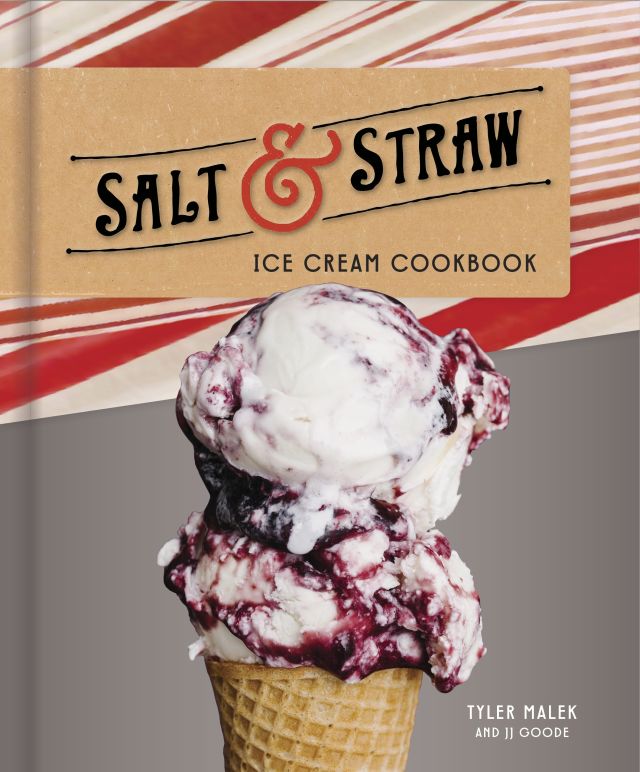

Making ice cream at home is already enough of a mental hurdle—you would not think that churning flavors like “blood pudding” and “cauliflower garam masala” was doable (or desirable) for your average cook. But Salt & Straw is out to prove us wrong with a new cookbook, due out from Clarkson Potter in April 2019. And according to Tyler Malek, one half of Salt & Straw (cousin and co-owner Kim Malek runs the business side), making crazy ice cream flavors is more than doable—it’s addictive.

We sat down with the 31-year-old Malek to hear more.

Who’s this book for? Is it an ice cream bible or a coffee table book?

We’ve been scared away from making ice cream for so many different reasons. You go to Goodwill and see how many ice cream makers are on the shelves. That’s not right. I wanted to break that barrier. The reality is that if we mix cream and sugar together and put it in our freezer, in some way it’s going to be ice cream. From there we can make it better, obviously. In my dream world, this book makes ice cream making accessible. But more than anything, people will want to read this and make their own versions with their own changes.

Since ice cream is such a specific, non-seasonal topic, how did you organize the chapters?

We have this tempo with our Salt & Straw menu that’s critical for how you experience our product. The seasonal menu changes every four weeks, just kind of telling the zeitgeist of what’s going on with local partners, local nonprofits, even the nearest elementary school. We wanted to figure out how to integrate that into the book itself. I had this very lofty goal that someone would read it from front to back. If you do, you have a sort of momentum. You climax somewhere right in the middle of the book. It calms back down and has this really heartwarming menu (The Student Inventor Series) towards the end. That’s how I think about the year and the menus I bring to Salt & Straw. The very first recipe in the book is critical in that it is both the most beautiful and simple: our olive oil ice cream. In many ways it’s even more simple than vanilla ice cream. The idea is to build skillsets and slowly make people more comfortable with making ice cream.

What was the hardest recipe to develop?

I think the third chapter (The Brewer’s Series) as a whole. It’s both the hardest and the most fun challenge I’ve gone through in our flavor development process; imagining how craft brewing can integrate itself into ice cream. It was the most eye-opening thing in my career. That idea of truly learning from their process. Why wouldn’t hops work in cream? Why does it only work in alcohol? There’s something so foundation-setting about how we think about flavors in that chapter.

Tyler Malek

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

The base recipe has both xanthan gum and corn syrup. Is that something for health-conscious Portlanders to worry about?

This is as close to the ingredients we use at Salt & Straw as you can find off the grocery shelf. We use a couple of other gums, for different reasons. What makes really great ice cream so great is a dynamic variety of sugars. The reality of corn syrup versus high-fructose corn syrup is that they are night and day different—one has gone through a chemical process, and the other has gone through a cooking process.

Custard in itself has its own, great flavors. We actually use it in the Meyer Lemon Blueberry flavor. But if I want to make a pear and blue cheese ice cream where the pear just blows up and you taste all the floral flavors, you can’t have eggs in there competing. Pretty much anything that’s not chocolate or vanilla or lemon—custard will get in the way. It’s also a far easier process without eggs.

How do you dream up your conceptual flavors, like “Essence of Ghost” or “Dracula’s Blood Pudding”?

The idea is less about amazing ingredients and more like “how do we bring this spirit—this intense mystery in ice cream—forward.” To do that we really had to dig deep into how we think about the flavors. The Love Potion and the Ghost are good examples. If you’re going to call this a “love potion,” what should you “sense”—not necessarily taste—when you eat the ice cream? How does the back of your spine feel when you put it in your mouth? When your teeth bite through it, what are those textures?

You now have 18 shops in six different cities. What’s the game plan?

When we first started growing outside of Portland, we told ourselves, “If we grow outside of Portland, each shop has to have its own voice in the product.” When you go to LA, its menu should look dramatically different from Seattle, where we are working with Beecher’s Cheese and Rachel’s Ginger Beer. Because that’s what the city demands. That’s what the menu needs to be to lift up the food community around it.

When we opened in Disneyland, our initial instinct was to dumb down the menu. We thought, “We can’t serve bug ice cream down here.” Three weeks before we opened, we said, “No. It’s important for us to stay true to who we are.” It was really terrifying. But within two weeks, the Disneyland location sold more bug ice cream than three of our other scoop shops combined. It was mind-blowing for us.

As we grow, if we can help amplify people’s days, and be a space where it makes you happier, and we help change the community around us, that’s pretty cool. And I don’t think we can do that if we’re open on every corner. I don’t know that we could even do that in Portland if we opened too many more locations than what we have now.

Growth for us is not nearly as prolific is many other brands out there. Think of Sweetgreen—they’re opening 30 shops a year. We are opening four or five. I think the Disney shop is arguably both the most architecturally beautiful shop in the world and also the busiest ice cream shop in the world. And at the same time, to be selling this insane menu that’s talking about all the local purveyors and this bug farm in Oakland, that’s neat. To know that we haven’t had to undercut our values from that perspective is pretty inspiring.