The A to Z Food Lover's Guide to Oregon

This time of year, it’s easy to love Oregon’s food scene. Farmers markets—seemingly everywhere, every day—overflow. Restaurants that make Northwest crops their religion (or at least their business model) glory in the bounty from our fields and orchards. A short drive from Portland in just about any direction leads to a sweet apple grove or a vineyard gearing up for crush. In this special feature, we celebrate all that seasonal splendor. But we also meet some of the adventurous farmers and high-craft entrepreneurs who create the products and projects that drive Oregon food. We see how global trends influence what grows here (Korea is obsessed with our blueberries). And we check in on some of the ideas and issues that will shape our culinary landscape in the years to come.

A is for Ancient Heritage Dairy

The state’s most old-school cheese operation goes urban.

B is for Bacon

We round up our four favorite locally made strips for the ultimate DIY brunch:

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

From top to bottom:

Laurelhurst Market Irish Bacon

This relative of Canadian bacon (a.k.a. pork loin) comes with a slice of fatback attached. It’s not as fatty or salty as belly bacon, and has a slightly toasted quality.

Chop Bacon

Textbook belly bacon; super smoky, fruity, and juicy

Tails & Trotters Bacon

Thick-cut, hazelnut-finished pork, cured with a clove-nutmeg-cinnamon mix, aged for two to six weeks for a deeply porky, umami-rich, almost herbal flavor

Pono Farm Jowl Bacon

Marvelously fatty, praline-sweet cheek bacon, soaked in a brown sugar brine for two weeks and smoked over cherry or apple wood

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

C is for Cider Boom

Introducing four new local heroes in the hard-cider revolution

Swift Cider’s CTZ Pineapple Dank Hop: Formerly sold as OutCider, Aidan Currie’s Northeast Portland cidery returns with a small but mighty line of cold-fermented, unfiltered, and unpasteurized hard ciders. This dry-hopped offering blends CTZ hops and organic pineapple juice to please even the most die-hard beer devotees.

Cider Riot!’s BurnCider: If you find most American-made ciders a bit too sweet, check out Abram Goldman-Armstrong’s offerings, inspired by the bone-dry ciders of England’s West Country, using Oregon-grown traditional English cider varietals and mouth-puckering wild apples.

Alter Ego Cider Original Off-Dry: Fermented by seasoned winemakers Anne Hubatch and Nate Wall at Southeast Portland’s new urban winery Coopers Hall, Alter Ego’s flagship off-dry cider has a touch of sweetness and tons of Northwest character.

Reverend Nat’s The Passion: Nat West is the king of blending traditional ciders with experimental flavors, from hops and apricots to ginger. Here, the Reverend adds a hefty dose of passion fruit for a tropical punch in the mouth.

D is for DeNoble

Tom DeNoble explains how DeNoble Farms, his Portland Farmers Market mainstay known for its Italian artichokes and addictive carrots (really!), stands out:

“The soil in Tillamook hadn’t been row-cropped for years. It was dairy, and between all those cows and the river floods, we have amazing soil. And then, 70 percent of everything we sell is harvested by me, my wife, or my kids. We’ve figured out how to pick at the height of flavor for the market. Being on the coast, where the salt water meets freshwater and a cool fog belt often comes in on really hot days, we often have flavors and varieties that no one else has.”

E is for Elder Hall

Ned Ludd chef Jason French raised more than $60,000 on Kickstarter to fund a communal food hall behind his Northeast Portland restaurant. Elder Hall will serve as a space for meetings, lectures, tastings, intimate dinners, raucous parties, and teaching events, all focused on Portland’s farm-to-table and artisan-infused culinary culture. A full commercial kitchen also is in the works, along with food-centric children’s summer camps, butchery and cooking classes, and a series of “small suppers” that showcase local foodie talent. “There are a lot of event spaces in Portland,” French says, “but not many have a full kitchen and an attached chef.”

... & also for Exports

About a decade ago, South Korea went blueberry crazy. “It was a country that embraced healthy food early, and really keyed in on blueberries,” recalls Bryan Ostlund of the Oregon Blueberry Commission. “In Seoul, McDonald’s had to have blueberry pie.” Naturally, America’s biggest blueberry-growing state wanted in on the action. Years of negotiations over crop safety later, Oregon became the only state allowed to export fresh blueberries to South Korea. Launched in 2012, this niche trade could send1.5 million pounds of Oregon berries to Korea in 2014, feeding that country’s antioxidant fascination. “It’s crazy-cool to see,” says Ostlund. “Blueberry skin cream, blueberry pet food, blueberry everything.” Possible future targets? The Philippines, Vietnam, Australia, and China.

Image: Courtesy Finex

F is for Finex

The Portland-made octagonal cast-iron skillet sizzled from crowd-funding to a 4,000-square-foot Northwest fabrication facility. “People have an emotional connection with cast iron’s heritage,” says CEO Ron Khormaei, “but they don’t want something that looks like it came off the Oregon Trail. This allows them to have a totally modern heirloom.” An eight-inch model joins the 12-inch original this fall.

G is for GMO Battles

Last October, Gov. John Kitzhaber signed a law limiting local governments’ ability to regulate seeds, meaning any future policies on genetically modified crops must be made at the state level. Exception: Jackson County had already scheduled a spring vote on a GMO ban—which then swept to victory with 66 percent in favor. A governor’s task force is crafting statewide legislation for debate in 2015. But voters’ apparent furor over the issue may yet prevail: 150,000 petition signatures mean an expensive November election fight over an initiative that would require labeling of GMO products in the state.

... & also for Goat Therapy (It's a thing!)

"It’s a dichotomy: urban life meets a farm-ish sanctuary,” says Christopher Frankonis, co-owner of The Belmont Goats. “A visit to the goats makes a good day better, or a crappy day bearable.”

Image: Courtesy Shutterstock

H is for Hazelnuts

China’s blossoming love for salted-nut snack packs—can you blame them?—means torrid times for one of Oregon’s iconic crops: Over the past five years farmers planted a combined 15,000 new acres of the nut also known as the filbert. At Oregon State University, the world’s preeminent hazelnut breeding program continues to churn out high-yield strains resistant to disease and fit for the Willamette Valley’s soil and climate.

... & also for Hotshots

Introducing a handful of upstart food companies making waves at Portland area farmers market this season—and where to find them.

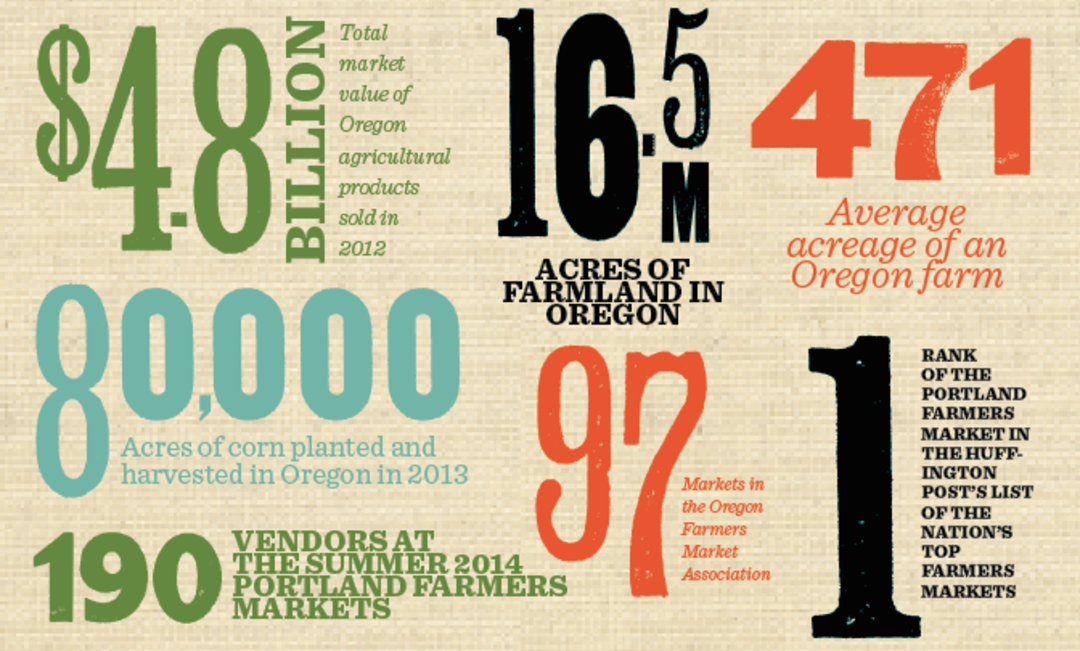

I is for Industry

Oregon agriculture encompasses small farms, big business, microharvests, and commodity crops.

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

J is for Jacobsen

How many artisan products can Ben Jacobsen, Portland’s wildly successful salt tycoon, churn out of the Pacific Ocean? His company’s latest, sparkling mineral water, is made from evaporated seawater, reconstituted with minerals from the salt-making process, and carbonated. “We are shooting for the sweet spot between German Gerolsteiner and Italian San Pellegrino,” Jacobsen says. Jacobsen’s water is crisp, refreshing, and—although he says this is impossible—distinctly briny, like an oyster. $3.50 at Zupan’s Markets

K is for Kombucha

Make your gut hapy with these five fermented phenoms we're loving this month!

Image: Thomas Cobb

L is for Lostine

Discover why locavore crusader Lynne Curry opened Eastern Oregon’s first farm-to-table restaurant in a one-horse pit stop on the way to Oregon's magnificent Wallowa Mountains.

Image: Allison Jones

M is for Markets

The Saturday Portland Farmers Market at Portland State University is a thing of beauty. The butcher, the baker, even the liquor store: it’s all here in hyperlocal Technicolor. But because not every day is Saturday, we’ve compiled a handy hypothetical planner for enjoying local market bounty seven days a week.

Image: Allison Jones

N is for Night Market

There are many great things about Feast, the annual conclave of foodie big shots that makes Portland the center of the American culinary-industrial complex for one weekend in September. But the three-year-old festival’s Southeast Asian–inspired Night Market (Sept 19) may best capture the whole affair’s gluttonous glamour. This year features Portland’s perpetual Thai dynamo, Andy Ricker, along with street-food turns from Night Market newcomers Ox, Nonna, Austin’s Uchi, and LA’s famously bombastic Animal. According to Feast cofounder Mike Thelin, the night’s new location could also be a star: “We’ll be on South Waterfront, looking north toward downtown. As a native Portlander, it makes me pretty darn proud to be part of one of the first big events in this part of Portland.”

O is for Oenophiles

Portland’s cognoscenti pick favorite off-the-beaten-path bottles.

Image: Kate Madden

Sarah Egeland | Smallwares

2012 Minimus Wines 43 Days, $18–23

“The most interesting sauvignon blanc I’ve tasted: flavors of rusty metal and ripe melon straight out of the summer sun ... more exotic and thought-provoking than anything any other winemaker is doing in Oregon.”

Joel Gunderson | Coopers Hall

2011 Fausse Piste Roussanne L’Ortolan, $27–33

“It’s exciting when a winery takes a chance on a varietal without large market appeal, then produces a distinct and lovely wine with it. Slightly intemperate in its youth, it’s matured into something seamless, yet memorable.”

Colin Howard | Oso

2012 Montebruno Pinot Noir, $25–27

“This wine starts like a good conversation—inviting and curious, it leaves you leaning in for more and more. It has Burgundy elegance with Willamette Valley character, at an amazing value as well.”

Dana Frank | Ava Gene’s

2012 Ovum ‘Suspension’ Muscat, $19–25

“Muscat is tricky—it can be soapy and hot. But John House and Ksenija Kostic coax some great acidity and brightness out of their old-vine fruit from the Eola Springs Vineyard. It’s fantastically balanced and fresh, yet rich at the same time.”

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

P is for Pantry

14 Oregon-made kitchen cabinet essentials, from guajillo chile oil and spicy Thai peanut butter to marionberry espresso jam and addictive granola.

Q is for Quest

The driving force behind the decades-long push to build a public market can practically smell success. In 2016, construction will begin on the James Beard Public Market, a 60-plus-stall permanent food hall at downtown’s Morrison Bridgehead. According to Ron Paul, the former city hall staffer who has pushed the idea since the 1990s, the vision would provide a showcase for Oregon food and an affordable market near public transportation.

Why do we even need a public market? Don’t farmers markets have us covered? At a farmers market, growers have to sell what they produced in person. At a public market, you might have those same growers represented but they don’t have to sell their food themselves. They could form a co-op, or be the pipeline to a grocer, butcher, or cheese monger. This increases farmers’ avenues of distribution.

Why now? Portland’s self-image has changed. Food coverage has helped change it. When food columnists in the New York Times talk about Oregon, people listen. Now we’re on the map, even though nothing on the ground changed. It’s just some other authority acknowledged it.

How do you make sure people don’t get priced out? To keep prices down, we’re committed to building the market without long-term debt. City, state, and federal dollars will all come into play, and we will roll out the ability for every family in Portland to own a share of the market. We’re not sure how they’ll be priced, but they’ll be reasonable enough so that every family can consider at least token participation. We call it the community ownership model.

Why not just find investors? From my years in the food industry, I realized the word “public” was in public market for a reason. It needed to be a partnership between public and private sectors. It would never work as a traditional business development if we want to maintain our goal of equity, access, and not wanting it to be a yuppie food hall.

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

R is for Recipes

Basque Potxa Beans

Potxa beans, pronounced “poh-cha,” hail from the Navarra region of Spain, where Viridian Farms’ Manuel and Leslie Recio source many of their prized varietals. These freshly plucked beans, available only July through October, lend a nutty, flavorful edge to this traditional Basque seafood dish. (Serves 4)

- 1 lb fresh Potxa beans (available at the PSU Farmers Market)

- 1 pinch salt, plus more to taste

- 1 green onion, root end removed

- 1 carrot, peeled

- 1 green pepper, cored and deseeded

- 2 tbsp olive oil

- 2 garlic cloves, minced

- 1 lb clams, soaked in cold water for 15–20 minutes

- ¼ cup dry white wine

- 3 tbsp tomato purée

- ¼ cup Parsley, chopped

1. Place beans, onion, pepper, and carrot in a pot, and cover with ½ inch of water and a pinch of salt. Simmer for about 30 minutes or until cooked through, but still firm.

2. Put the pepper, onion, and carrot in a blender, and purée with ¼ cup of the cooking liquid. Drain beans and set aside.

3. In a large pan, heat olive oil over medium heat and sauté garlic until golden, about 2 minutes. Add wine and boil until the alcohol has evaporated, about a minute longer. Add clams, cover the pan, and cook until they are open, about 2–3 minutes. Discard any clams that don’t open.

4. Add cooked beans, puréed vegetables, and tomato to the clams, and remove from heat. Mix well and let sit 3–5 minutes. Season to taste with salt, sprinkle with parsley, and serve immediately.

Grilled Steak and Romaine with Tomato Vinaigrette

Courtesy Lynne Curry of the Lostine Tavern, where grass-fed beef from Eastern Oregon is a menu mainstay. (Serves 4)

- ½ cup extra-virgin olive oil

- 2 small garlic cloves, minced

- 2 large beefsteak tomatoes, roughly chopped

- 2 small heads romaine lettuce, halved

- 2½ tsp kosher salt, plus a big pinch for the vinaigrette

- 1½ tsp smoked paprika

- ½ tsp black pepper

- 4 1-inch-thick New York strip steaks

- ¼ cup freshly squeezed lemon juice

1. Combine olive oil, garlic, and tomato in a small saucepan and cook over low heat until oil shimmers and garlic smells fragrant, about 5 minutes. Remove from heat.

2. Light a charcoal or gas grill over high heat. Brush romaine halves with tomato oil and grill, cut side down, until the bottom is well marked and the outer leaves are wilted. Cut out the core, slice into quarters, and set aside.

3. Mix kosher salt, paprika, and pepper in a small bowl. Pat steaks dry and season them on both sides with the salt blend. Grill steaks over the hottest part of the grill for about 3½ minutes on both sides for medium rare.

4. Transfer steaks to a cutting board. While they rest, make tomato vinaigrette: whisk lemon juice and salt into reserved tomato oil (with the chopped tomatoes included). Place a wedge of romaine and a few slices of steak on each plate and spoon the tomato vinaigrette over the top.

S is for Seed Science

Starting in 2010, a small team of growers, chefs, and researchers met in Portland to seek the best sweet red roasting peppers for Oregon’s organic farmers. They weeded out hybrid after hybrid until, finally, three varieties emerged above all others. When he brought them to market, one farmer, Frank Morton of Wild Garden Seed and Gathering Together Farm, saw pepper sales quadruple. The project, known as the Culinary Breeding Network, launched by Oregon State University agricultural researcher Lane Selman and plant breeder Jim Myers, glimpsed the potential of new varieties suited to local climes, demands, and tastes. The group has moved on to developing open-pollinated parsley, mild habanero, and winter crops such as chicories, cabbage, storage onions, and purple sprouted broccoli.

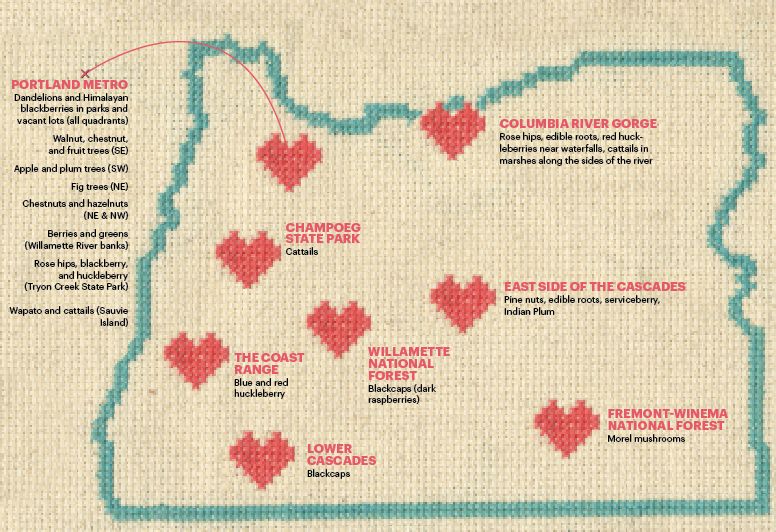

T is for Treasure Hunt

Farm country isn’t Oregon’s only culinary source. Foragers comb the state for wild eats—and while you’ll have to find your own patch, here are some hints on where (and how) to start the search.

Find edible treasure-hunting maps and tips in these guides:

Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast: Washington, Oregon, British Columbia & Alaska by Jim Pojar

Affectionately known as “the Pojar” after its author, this field guide details 794 species of plants found along the Pacific coast ($25).

Edible Wild Plants: From Dirt to Plate, by John Kallas

With wit, authority, and colorful photographs, local foraging expert John Kallas provides descriptions and recipes ($25).

Dandelion Hunter: Foraging the Urban Wilderness, by Rebecca Lerner

A Portlander’s personable and colorful guide to eating off the cityscape ($17)

App: “Wildman” Steve Brill’s “wild edibles” outlines descriptions, recipes, and dangerous look-alikes for 165 plants ($7.99 on iPhone, iPad, and Android).

U is for U-Pick Day Trip

Your destination: tiny Parkdale. “We had one Golden Delicious tree right by our house,” remembers third-generation Hood River Valley apple and pear grower Randy Kiyokawa. “Everyone wanted to pick one, so I thought, well, why not open the whole thing up?” Now Kiyokawa Family Orchards unleashes DIY pickers on scores of apple varieties through early November. Nearby, Draper Girls Country Farm hosts a rollicking Oktoberfest (Oct 4–5); drink fresh-pressed cider and take a dreamy, bountiful wander through their groves. Meanwhile, Solera Brewery pairs house ales with a killer Hood view.

Image: Stuart Mullenberg

V is for Viridian Farms

Thanks to a blend of Old World evangelism and Portland taste, one Spanish ingredient-loving couple has become a bellwether of local food culture.

W is for Winter

With Portland Farmers Market’s PSU mothership operating through December, PFM’s Shemanski Park Winter Market in January and February, and markets in Hillsdale and at People’s Co-op rolling year round, adventurous palates can cuddle up with:

Chicories: Radicchio and its bitter brethren shine after a kiss of cold. Lane Selman of Oregon State’s seed program and Gathering Together Farm says: “Spring Hill Farm grows a beautiful chicory salad mix. Ayers Creek Farm grows the best Treviso tardiva (a rare Italian radicchio) in the country.”

Turnips and rutabagas: “Gathering Together grows the gilfeather turnip and the Joan rutabaga,” Selman says of these sweet-spicy underground dwellers.

Celery, parsley, and cilantro roots: Intensely flavored, gnarly looking, loved by chefs. Available from most winter-going market farmers, such as Persephone, Groundworks, and Spring Hill.

Kale: Well, of course—but new-minted clichés aside, Portland’s winter markets are a rainbow family of kale varieties; the crinkly, deep-green leaves of Siberia may be particularly apt once temps plunge.

Image: Courtesy Shutterstock

X is for Xerces

What would Oregon’shomegrown food scene look like without native pollinators? Grim. “What’s summer without blueberries and raspberries?” says Mace Vaughan of the Portland-based Xerces Society, the world’s leading invertebrate conservation group and a frontline player in the battle to save agriculture’s winged assistants.

The situation is increasingly dire. In 2013 and 2014, approximately 100,000 Oregon bumblebees were killed by neonicotinoid insecticides—the most widely used and longest-lasting agricultural pesticides in the world. In March, Gov. John Kitzhaber signed the Save Oregon’s Pollinators Act into law, regulating—and eventually discontinuing—four types of these pesticides. The Xerces Society supported the bill, but members don’t think it goes far enough.

Xerces offers instructions on how to create habitat for the native pollinators our food supply depends on. Vaughan notes that without native pollinators, many aspects of Oregon’s high-quality agriculture sector would suffer; even grass-fed beef largely depends on bee-pollinated clover and alfalfa. “A number of bumblebee species in North America are highly endangered, and at least one is likely extinct,” says Sarina Jepsen, Xerces’s Endangered Species Program director. “Seven of the 25 Oregon species are at risk of extinction.”

Y is for Young Farmers

Three crucial programs train a new generation of growers.

WWOOF: One hundred Oregon farms offer short-term instruction to volunteers, many of whom Wwoof (Worldwide Opportunities on Organic Farms)—yes, also a verb—to travel. But some seek to learn the business. “Younger volunteers tend to say they hope to own their own farm someday,” says Karen Silbernagel of Clackamas River Farm, which relies on between one and three Wwoofers at a time.

Food Waves: Internships from May through September on 5.8 acres near Estacada are designed to suit academic pursuits. “If you’re studying horticulture at OSU, we can give you practical experience,” says co-executive director Matthew Brown. Food Waves sells produce at the Portland Farmers Market at PSU and the West Linn Farmers Market.

Food Works: High school kids learn farming in summer and year-round programs, from planting starts to marketing the organization’s CSA. “They get their hands dirty and work as a team, and take those skills on to whatever comes next for them,” says supervisor Mikael Brust. Find Food Works at the PSU and St. Johns farmers markets.

Z is for Zeitgeist

Anthony Boutard of Ayers Creek Farm on Oregon food culture, circa right now:

“We’re in a maturation phase. Farms are transitioning to being less subject to trends. Once, you’d have these trendlets wash over you—microgreens, or whatever it would be at the time—and they’d just bedevil you. Quick: how do you grow microgreens? Now you have a lot of farmers who have done direct-sale and farmers markets for years. The knowledge base is there—it’s not about chasing trends. At our farm, we’re growing our own grains, primarily wheat and corn, and sluicing those into our selection so we have stable year-round income.

“If the premise behind farm-to-table is correct—that there is higher quality to be found, and that pursuing it reflects well on the businesses that do so—then it will prove very durable. We have a few aphorisms we use here, and one of them is ‘don’t believe your own rhetoric.’ In other words, don’t just say that these fresh-picked berries are good because they’re fresh—taste them. ‘You’re only as good as your next turnip’—that’s another one. If the quality is high, people will buy it. If the quality slips, they’ll wonder why they’re paying more, and they’ll go elsewhere. It’s up to the farmers.

“We’re building a palate among young people. My mother was English, so I had to eat curly-leafed kale, but otherwise no one touched the stuff. She had to grow her own. Now we have a whole generation of kids growing up aware of these rich, lovely, complex foods. They’ve been getting ’em since the womb. I have customers whose mothers started buying from me when they were pregnant who now walk up, on their own, and make their own choices. I don’t think they’re going to give that up."